[

]

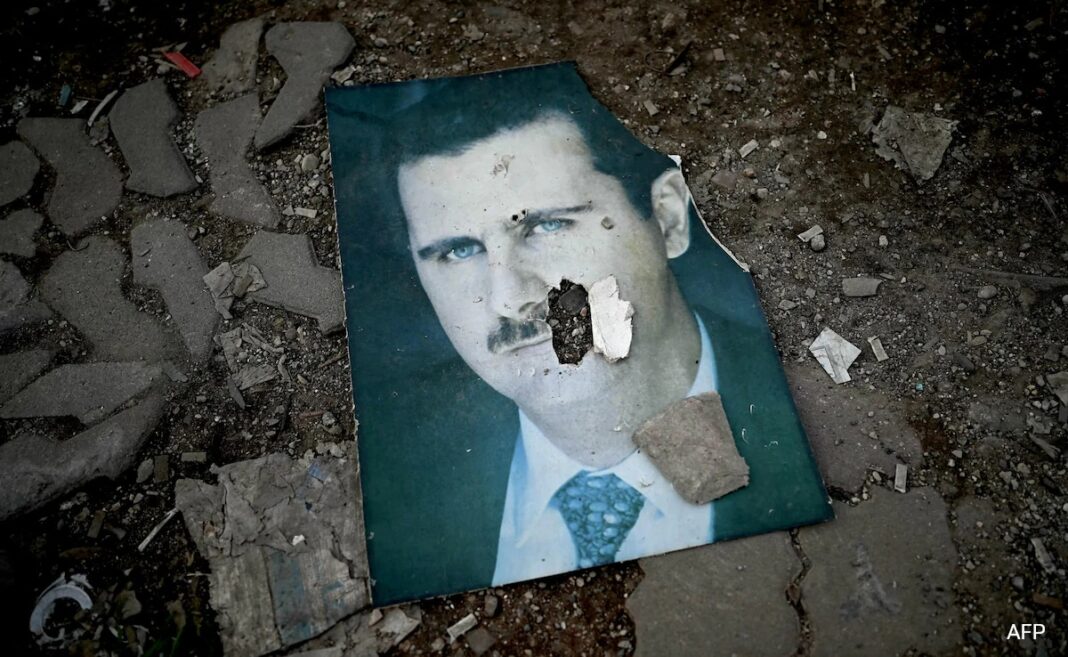

The drive winds between manicured lavender-lined lawns to a crescent-shaped home with a gleaming swimming pool on the Syrian coast: Bashar al-Assad’s holiday hideaway disgusts those who now come here.

“To think that he spent all that money and we lived in misery,” spat Mudar Ghanem, 26.

He is grey-skinned and his eyes are sunken after spending 36 days in a Damascus jail, accused like other suspected dissidents of “terrorism” against the ousted president’s rule.

Now he had come “to see with my own eyes how they lived while other people had no electricity”, Ghanem told AFP, standing by the windows of a huge white-marbled living room.

“I don’t care if the next president lives here too,” he added, “as long as he looks after the people and doesn’t humiliate us.”

The Assad holiday home is in Latakia, Syria’s second largest port after Tartus. It is in an area that is the heartland of the Assad clan’s Alawite faith, an offshoot of Shiite Islam.

On Sunday, a week after the deposed president fled Syria a lightning rebel offensive after his family had ruled for more than five decades, curious people came to see how Assad had lived.

This was just one of three Assad villas on the outskirts of the city.

In scenes that were unimaginable just days ago, Syrians wandered through the luxury home that is now guarded by a handful of former rebels.

There was no air of triumphalism, just stupefaction and anger at how Assad had lived a life of luxury in this idyllic seaside spot.

Over the past week the house itself has been ransacked, stripped of its last doorknob, but the grandeur of its rooms and the antique mosaic adorning the entrance bear witness to its standing.

Showroom

The land used to be owned by Nura’s family.

“They chased us away. I didn’t dare come back” before now, the 37-year-old said, adding that she intends to seek legal redress to get her property back.

Most people who spoke to AFP on Sunday, like Nura, spoke freely but preferred not to give their full names. Despite its downfall, the fear instilled by the Assad name is still there.

“You never know — they could come back,” said 45-year-old Nemer, after parking his motorbike outside a flashy villa.

The house belonged to Munzer al-Assad, a cousin of the former leader.

Along with his brother, who died in 2015, Munzer ran the notorious “shabiha” militia, known for its abuses and trafficking operations.

“It’s the first time I’ve stopped here,” Nemer said. “In the past the guards would chase us away. We weren’t allowed to park.”

The two-storey house had also been stripped. Chandeliers, furniture, stucco mouldings… all gone. Family photographs ripped up and portraits torn from now bare walls. The looters had been busy.

“I get 20 dollars a month. I have to do two jobs just to feed my family,” Nemer said, bitter at the memory of Assad clan convoys that used to speed through the city streets.

Munzer’s son Hafez ran a car showroom — Syria Car. Now just a single vehicle sits there among the broken glass.

The car won’t start, so people have been pulling it apart, destroying its bodywork, windows and upholstery. A young couple pretended to get behind the wheel.

On a mission

Lawyer Hassan Anwar, another visitor, was on a mission. The 51-year-old inspected the premises, searching for any documentation that could be later used in court.

He said this was because Hafez was well known for confiscating cars or buying them for well below market price before selling them on.

“Several complaints have been filed,” Anwar said.

“Syria Car” was in fact one big money-laundering operation to mask the family’s trafficking operations, the lawyer said.

On the pavement outside, two passers-by stopped beside a sewer grating. They lifted it up and scooped out hundreds of small white pills.

This was captagon, a banned amphetamine-like stimulant. It became Syria’s largest export, turning the country under Assad into the world’s biggest narco state.

They said massive quantities of the drug had been found nationwide after Assad fell.

Lawyer Anwar said pills had been exported from Latakia inside clothing labels.

Accompanied by two young rebels newly arrived from Idlib province, Anwar entered the building beside the showroom, stepping through its broken window. As he did so, a young guard, Hilal, appeared.

In the basement, Hilal had discovered brand new scales still in their boxes — “for weighing drugs”, he said — along with box after box of glassware, pipettes and tubes he said were used to manufacture amphetamines.

“I’m shocked by the scale of these crimes,” said 30-year-old Ali, one of the two fighters from Idlib.

As Ghanem said at Assad’s sumptuous holiday villa, standing there and looking out to sea, “God will have his revenge.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)